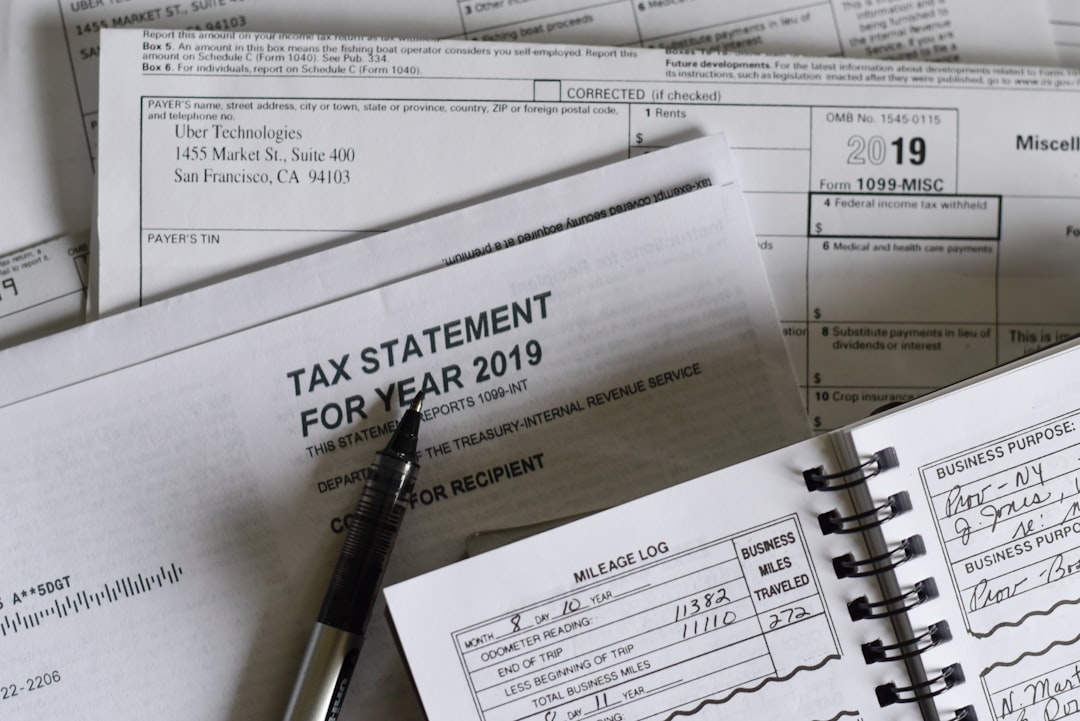

Happy Tax Day! Or if you’re like me and navigating taxes while self-employed: condolences. I thought that being in a lower tax bracket meant that I would pay a lower percentage of my income in taxes (because that would make sense, right?), but it turns out this is just further evidence that I am terrible with money and finances.

How could that be, Cece? You may be asking. Your school and career decisions were calculated for high earnings!

Ahh, yes—a popular misconception. Making a lot of money does not mean you are good with money. High-earners of the salaried variety come in two flavors: (1) those who are really good with money management and personal finances and (2) those who are so scared of money, of thinking about it, of facing its finitude, that they would do anything to not think about it—including studying for years and years, gunning only for extremely high-paid jobs, and welcoming the detachment and delirium that come with working through t…