I originally titled this, “Paul, Skadden, Willkie, and Milbank are the Four Horsemen of Democracy” after the four Biglaw firms (Paul Weiss, Skadden, Willkie Farr, and Milbank) that struck deals with the Trump Administration instead of fighting the likely unlawful executive orders and actions. But as I edit this—and who knows what will happen in the months to come—five more law firms have bent the knee, including the most profitable firms in the world (and one I used to work at).

The firms’ justifications for striking deals—they would never call it capitulating—are all some sort of variation on protecting our clients’ interests, protecting our employees, and protecting the Firm. But what about protecting democracy and the rule of law?

Four of the five firms in this second cohort agreed to provide $125 million in “pro bono and other free Legal services” (emphasis added). (The prior arrangements were only for “pro bono Legal Services.”) Which begs the question: What will these other free legal services be for? What could they possibly be?

But what really takes the cake is the part of the agreement where the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) withdraws its demand letter to the law firms, seemingly in exchange for free legal services. Are we really now in a country where Biglaw firms pay the Administration via free legal services in return for dropped inquiries?

I get that institutions want to survive. But when this myopic survival instinct contributes to the erosion of the rule of law, perhaps it is better to simply die with honor. Die and not ruin democracy for everyone else.

Because you know what I’m really going to be happy about when bribery and corruption run rampant in government? That the institutions of Cadwalader, Kirkland & Ellis, Latham & Watkins, A&O Shearman, and Simpson Thacher survived. Praise be.

But first, let’s back up for those who haven’t been glued to Biglaw news in the past weeks. Why are Biglaw firms striking deals with the Trump Administration in the first place? Because the Administration proactively targeted 20+ Biglaw firms through executive orders and an EEOC letter. The executive orders vary slightly in language, but the crux of the Administration’s position is that certain Biglaw firms “take actions that threaten public safety and national security, limit constitutional freedoms, degrade the quality of American elections, or undermine bedrock American principles.”

They do this—the executive orders argue—through pro bono work, representing “failed Presidential candidate Hillary Clinton,” and hiring Robert Mueller and his colleagues “after they wielded the power of the Federal Government to lead one of the most partisan investigations in American history.” As a result, these firms “should not have access to our Nation’s secrets, nor should such conduct be subsidized by Federal taxpayer funds or contracts.”

The executive orders then levy four punishments:

suspending any government security clearances held by the target firms’ lawyers;

requiring government contractors to disclose whether they conduct business with a target firm, and if so, taking steps to terminate those relationships;

be investigated by the Attorney General and EEOC for racial discrimination in hiring summer associates, promotion, and attorney development opportunities; and

limiting the target firms’ access to “Federal Government buildings” (which would presumably include courthouses) and limiting employees of the target firms from seeking government jobs.

Make no mistake—for some law firms, this would be catastrophic. If a firm’s government contracts work accounts for a substantial percentage of their revenue, then an executive order like this could very much be a question of corporate life or death. If a firm’s M&A practice heavily depends on CFIUS approval, I can appreciate how abjectly scary the idea of being in Trump’s crosshairs is.

But the problem is that Paul Weiss, Skadden, Willkie Farr, Milbank, Cadwalader, Kirkland, Latham, A&O Shearman, and Simpson Thacher—yes, I’m going to continue listing their names, because they should be publicly connected to their actions—they are not firms knocking upon death’s door. They are among some of the most profitable firms in the world, year after year.

Kirkland’s revenue last year was $8.8 billion. Profits per equity partner (PPEP) were reportedly $9.25 million. Latham had revenues of $7 billion. Paul Weiss had PPEP of $7.5 million. In 2023, Simpson Thacher’s PPEP was a cool $6.4 million and Skadden’s was $5.4 million. Milbank and Willkie Farr weren’t far behind, at $5.1 million and $3.8 million, respectively. And if you’re a partner at Cadwalader or A&O Shearman, you’d be the poor ones of the bunch—with PPEP of only $3.7 million and $2.6 million.

(And I know I’ve written before about how PPEP distorts attorney compensation, but my point here is PPEP is still a telling indicator of how overall wealthy a firm—and its equity partners—is. These are not people without savings—and if they are, they really should get a financial advisor.)

Which is why it is laughable to read Brad Karp’s letter to “the PW Community”—because you can always count on controversial news being addressed to a community—wherein he discusses the “existential crisis” Paul Weiss would face if subject to the executive order:

Only several days ago, our firm faced an existential crisis. The executive order could easily have destroyed our firm. It brought the full weight of the government down on our firm, our people, and our clients. In particular, it threatened our clients with the loss of their government contracts, and the loss of access to the government, if they continued to use the firm as their lawyers. And in an obvious effort to target all of you as well as the firm, it raised the specter that the government would not hire our employees.

This, folks, is fear-mongering at its finest. A veritable masterclass, really. In one paragraph, Karp manipulates and circles in on the reader’s growing sense of dread, as if the Jaws theme were playing in the background. He goes from fears about the firm (“could easily have destroyed our firm”) to fears around the firm (“threatened our clients”) to—finally—you. The intent is to instill fear and then to sell the solution (the deal with Trump) directly to you.

So I will give Karp that: he’s clearly a good salesperson. And of course he would be—he’s chairman of a law firm with over 1000 attorneys and revenue of more than $2.6 billion! You don’t become chairman of a Biglaw firm by simply being an excellent lawyer; you must also be an excellent salesperson.

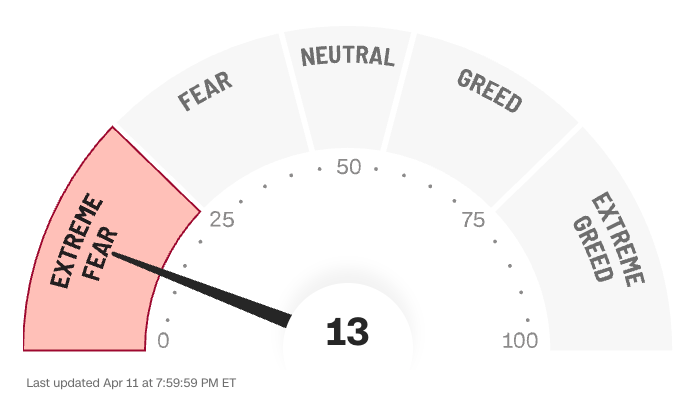

No surprise, then, that Karp’s letter alternates between stoking feelings of Fear and Greed. The Fear-Greed axis isn’t new, although once you know about it, you’ll start seeing it everywhere. Developed in 2012 by CNN, the Fear & Greed Index is a simple barometer of market sentiment for risk appetite. When Fear dominates, the market sees stock sell-offs and purchases of safer assets like Treasury bonds. When Greed dominates, the market buys stocks and makes riskier investments. (Unsurprisingly, the index over the past month has been at “Extreme Fear” or “Fear.”)

The commonality between Fear and Greed is that they are strong motivators to get people to act, to engage, to do (usually buy) something. If you were happy, you’d be enjoying your life—spending time with loved ones and making tasty food together—not panic-purchasing canned food and toilet paper for your bunker. Happy people don’t panic-purchase; they just don’t. But fearful and greedy people?

In this way, Fear and Greed are extremely useful in advertising and marketing. They are two of the most powerful emotions when it comes to selling something—products, subscriptions, even ideas. Pay attention the next time you’re served an ad or presented with a sales pitch. Does the language exploit feelings of “lack, scarcity, and the urgency of resolving a problem?” It’s a bid for Fear. Or does the language appeal to “desires to acquire, retain and dominate?” Then it’s Greed.

And sometimes it’s both! When Karp highlights how alone poor Paul Weiss is in the legal industry, he’s invoking Fear; when he cites to other Biglaw firms coming for Paul Weiss clients and attorneys, it’s both Fear & Greed:

We were hopeful that the legal industry would rally to our side, even though it had not done so in response to executive orders targeting other firms. We had tried to persuade other firms to come out in public support of Covington and Perkins Coie. And we waited for firms to support us in the wake of the President’s executive order targeting Paul, Weiss. Disappointingly, far from support, we learned that certain other firms were seeking to exploit our vulnerabilities by aggressively soliciting our clients and recruiting our attorneys.

What makes me angriest is these are the exact law firms who could weather a financial setback. Karp claims, “It was very likely that our firm would not be able to survive a protracted dispute with the Administration.” It’s hard not to roll my eyes at this statement when Paul Weiss also reportedly paid a lateral partner $10 million one year. The claim also implies that we’ll “very likely” see the bankruptcies of Perkins Coie, WilmerHale, and Jenner & Block—three Biglaw firms choosing to fight their executive orders in court, under a shakier but still extant belief in the rule of law and democracy.

But this isn’t just to single out Paul Weiss. Only three of the top 100 law firms by revenue offered unconditional support in an amicus brief in support of Perkins Coie’s lawsuit challenging the executive order. None of the top 20 law firms have dared. And merely eight firms in the top 100 offered conditional support—one condition being that their closest peer firms also sign the brief.

I wish I could say this surprised me. But it didn’t. Those who are drawn to becoming lawyers love—or at least desire—rules. Given a choice between saying nothing or saying something and potentially breaking a rule, lawyers will gravitate towards the former.

I feel that fear in my bones, I really do—I am 100% certain that by posting this, I am closing off any last opportunity I may have to return to Biglaw. And I desperately want to cling onto that possibility, because I’m really scared about my future—I quit to pitch a book, and sold that book, but then lost that book deal—and there is such a large part of me that doesn’t want to deal with the emotional discomfort of living my own path anymore, that wants just to be told what to do and do it really well and never think again. Like, I want to be Paul Weiss! I want to be told I’m doing right by an authority figure and also make a ton of money!

I also understand that greed—that desire to acquire and retain and dominate—feels existential now. I am so afraid that if I don’t stock up on assets now, I won’t be ready when society falls apart. When I need money and resources to convince others to travel with me, when I need gold bars to bribe an officer at the border to let me cross into Canada, when I need $1 million for a ticket to Mars because the richest and wealthiest have decided to ransack and then abandon Earth. I’ve seen The Last of Us, Snowpiercer, The Handmaid’s Tale. I’m really fucking scared.

But I also know what I would pay for democracy, what discomforts my parents endured so they could live in a democracy, what I would give up to contribute to the rule of law, this country I really do love and call home even if thousands would tell me to go back from whence I came.

In Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), there’s a concept called willingness. Willingness means choosing to act consistently with your values, even if it feels bad—and a lot of the times, it will feel bad. But you don’t try to change or control that bad feeling. You just sit with it, and feel bad, and carry on anyway. Because there are some values in this world that are so important to you, so critical, that they are worth everything, even enduring your own bad feelings.

The pinnacle example of this? If your child—or dog, or cat, or someone else you really love—is in the middle of the road and cars are going by, do you stand to the side, wrestling with your own terror about running into the middle of the street? No—you run into the middle of the street. You just do it. It doesn’t matter how scared you are, how bad you feel—you just do it. And I care about your feelings, I really do—and we can talk about these bad feelings as much as you need to—but I also need everyone, especially the Brad Karps of the world, to exhibit willingness and live their values.

You don’t get to just live your values when it’s easy, when progressivism is in vogue. You have to live your values when it’s hard to do so, too, when it’s really scary and stressful.

Because it’s important to have that in mind, how much you’d give up to fight for the values you believe in. For the decision-making partners at Paul Weiss, Skadden, Willkie Farr, Milbank, Cadwalader, Kirkland, Latham, A&O Shearman, and Simpson Thacher—God, I hope there aren’t more law firms by the time I publish this that I’ll have to add the names of—the rule of law apparently had too steep a price. But for me, and you, we get to draw our own line. And I’m not going to tell you what it is, because it doesn’t matter what I think—what matters is that you set it, and you live by it. And be prepared to die by it. ◆

What You Can Do

Speak with me about what you’re seeing at your firm! If you’re involved in discussions about your firm’s response to the Biglaw-Trump Administration deals, fill out this form to speak with me on a de-identified basis. I’d love to hear how you are/your firm is navigating this and also provide you with whatever support and connections I can.

Engage in daily acts of resistance. This can be big, like sending a public email to the Chair or the media. It can be small, like speaking with a peer to signal your views. But make it something! Especially if you are more senior, talk to the partners with whom you work. Make your opinion known. Think on your values and decide at what point you would resign. And if it gets to that point, resign—or better yet, coordinate with your colleagues and make it a collective resignation. Collective action is hard, but it’s also what is needed.

Contact your law school’s career services. I recently spoke with HLS’s OCS about ways to better educate law students about the realities of lawyering, especially living one’s own values while lawyering. I even raised the prospect of sanctioning certain law firms from on-campus interviews if alums report certain inconsistencies with recruiting statements. As an alum, you have power!

Utilize these toolkits from the wonderful Rachel Cohen to organize and protest. The toolkits contain express steps for organizing, explicitly factoring in differing risk levels, and also contain template language so you don’t have to reinvent the wheel.

Thank you for reading debrief! If you enjoyed this post, consider upgrading your subscription or sharing this post:

Becoming a paid subscriber gives you access to my inner sanctum—essays and private podcast episodes on nascent ideas—as well as archival posts older than six months. Subscribing also helps ensure that my informational and educational video content on all other platforms remains freely available to all.

Please know, though, that having you here and being able to be in conversation with you is the most important thing to me. If you are a student without disposable income, un-or under-employed, or a minimum-wage worker, just email me or fill out this form and I’ll comp you a free subscription, no questions asked. If you’d like to donate one of these subscriptions, you can do so here.

Share this post