everything you wanted to know about embryo freezing (IVF) in new york city

the cost! my numbers! bodily changes!

“Egg and embryo freezing are not guarantees that you can have kids later,” my reproductive endocrinologist and infertility (REI) doctor told me the first time we met. “There is no perfect time to have children. If you know you want them, you should start trying for them now. You understand that, right?”

I stared at her, nodding more out of expectation than understanding. The way my friends talked about egg freezing, I viewed it as freezing a moment in time, like a photo. Aim the lens, press the shutter, click. Now you have that picture forever; now you can call upon that picture whenever.

“It is always better to try for kids earlier rather than later,” my doctor continued. “If you’re 40 and we implant all the frozen embryos and none of them take, then that’s it. We can try cycling again, but it will be much more difficult. You’ll be 40. It would’ve been easier at 38, even more so at 36.”

My throat tightened. I thought freezing embryos was supposed to make me feel better about my life, give me more time. Instead, my doctor was telling me that I was racing the clock regardless, even if I forked over months of my life and tens of thousands of dollars.

One of my New Year’s resolutions for 2025 had been to freeze embryos. N and I had been together for ten (!!!) years; while we individually always thought we’d have children, we were (and still are) in the midst of a crisis of faith about parenting as an endeavor. As we hiked up and down the trails of Patagonia, we reflected on 2024 and made plans for 2025. I would be turning 34, the age that a mere two years ago, I thought I’d surely be ready to have kids by. (How optimistic my 32-year-old self had been!)

Part of me wanted to wave away the Baby Question. Just two more years, and I’ll be ready. But the truth was I didn’t know, couldn’t know. If two years ago I thought I would’ve been ready by now, who’s to say that in two years, I would be truly ready? I recognized the Escher stairs forming, how this series of thinking would ultimately get me to exactly where I already was.

When we got back to New York mid-January, I asked my friends for doctor recommendations. N and I scrolled through educational credentials and fellowships, reading biographies and mission statements. I began calling clinics to make appointments, and I was glad to be starting the process early in the year—new-patient appointments were at least 1-2 months out.

Content Warning: The below will discuss pregnancy and detailed numbers of my fertility process, as well as bodily changes during and after. Please read with care.

My friends had warned me that the process would take longer than anticipated—plan for about six months after your first phone call, they said—but I was surprised at how much of that timeline was due to my own life being the limiting factor. Although I had to wait several months for my first appointment, it was full send afterwards. Blood draw, urine sample, transvaginal ultrasound, semen analysis, genetic testing for recessive genes—I went from not thinking about fertility at all to thinking about it multiple times a day, multiple times a week. If I’d truly devoted my life to the process, I could’ve been done with my first cycle in three months, phone call to egg retrieval.

Perhaps this was the first indicator of how I might struggle with parenthood, how unwilling I was to put the rest of my life on hold. It was the middle of the spring semester; I was commuting to New Haven weekly, as well as separating from my publisher. When the clinic’s nurses informed me I had to get the rubella vaccine before I could begin “cycling,” per the parlance, I didn’t immediately schedule the booster.1 It took me a month to finally get the vaccine, and then another month to figure out which 3-4 week period of my life wouldn’t involve travel.2

I kept reminding myself: Embryo freezing is minimally invasive compared to pregnancy and childbirth. And yet—I was barely able to rearrange my life for embryo freezing. I couldn’t fathom the extent of life tetris required for a breathing, needy, wailing baby.

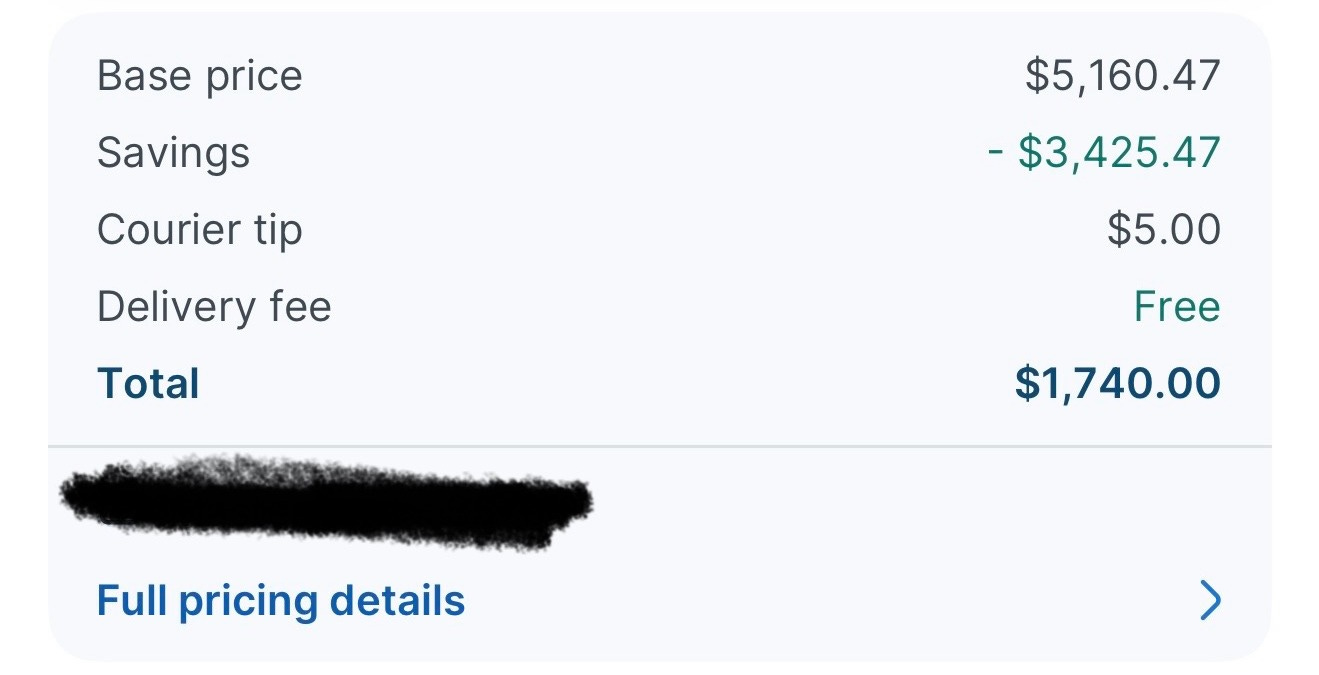

But I couldn’t let perfection be the enemy of the good. I ordered my first batch of fertility medications—enough for 8 days, the minimum number of hormone stimulation days—and scheduled my start date for the Monday following a wedding. My doctor prescribed me three different medications—Gonal-F, Menopur, and Ganirelix—at relatively low doses given my size and hormone levels, and still my eyes nearly popped out of my head when I went to check out:

A switch flipped within me. I tried to make sure I personally received packages from the couriers. If I was out of the apartment, I’d hurry back home the moment I saw the courier was close. I obsessed over unpacking the boxes and vials, reading and re-reading the storage instructions to make sure I placed every precious liquid into the correct climate. Every box felt like a possible hundred-dollar mistake.

I wondered if this was a preview of how new parents feel when the nurses thrust their newborns into their arms, suddenly seized by the full financial and emotional weight of what they’d gotten themselves into. I couldn’t ask for a refund anymore; I couldn’t screw this up now.

Before my injections, I told myself I was going to ignore the instructions against exercising. The nurses talked about the risk of ovarian torsion, but I dismissed them as silly. I knew my body; if I routinely worked out, why couldn’t I continue to do so, at least for the first week? Besides, the mental health benefits of physical exercise were too great—I didn’t want to fall into a depression, did I?

But on my start day (Day 1), I had a complete change of heart. After my blood draw and ultrasound, I booked my last exercise class in what would end up being a month. The sheer cost of the embryo freezing process was beginning to freak me out—being anything but absolutely strict with medical instructions now felt like tanking a very expensive investment, like buying a new car and immediately drunk driving.

Around 2pm, the nursing team called with my dosages for the day. Even after watching the numerous videos online demonstrating how to mix the Menopur and how to inject the Gonal-F,3 the thought of shots was still nerve-wracking. “You basically pay a ton of money to take home a DIY kit,” one of my friends explained.

Luckily, I’d lined up experienced friends on Day 1 and Day 2 to come supervise N and me as we swirled vials, tapped syringes, and stabbed my abdomen. We learned our own hacks and preferences, like icing the injection site ~30 minutes beforehand and injecting the Menopur as quickly as possible even if it burned more.

After my blood draw on Day 3, the receptionist asked if I wanted to pay for the cycle now or later. I shrugged. “Now’s fine.”

She told me the amount with a straight face. “Will you be paying by credit card?” she asked.

My eyes widened, but more so at her comment about paying by credit card. How many credit cards could accept such a huge, one-time cost without blowing through their credit limit? I’d received an estimate beforehand—I was prepared for the total cost—but for some reason, I thought payment would be via ACH or wire. Now my credit score and creditworthiness were also being tested.

I tried to appear nonplussed as I mentally shuffled through my wallet. Could I ask to split the cost over multiple cards? How embarrassing would it be if my card got declined? Surely it couldn’t be the first time that happened, could it?

I held my breath as I inserted my Amex into the card reader. Please, please, please… I prayed.